|

What are icons?

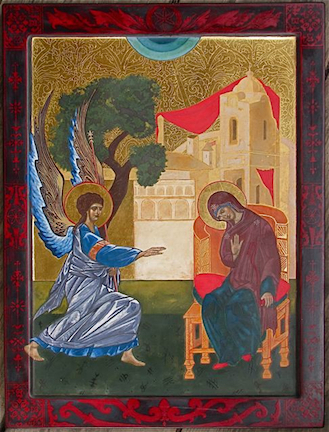

Icons are images of the divine and are found in all cultures throughout time. As windows into the spiritual realms, the archetypal stories and characters that icons represent find a deep reflection in our consciousness and open the doors of our perceptions. Since the early centuries of Christianity, the term 'icon' (image in Greek) has been used to refer to images with religious content, meaning and use. Many people assume an icon must be in a Byzantine or Russian style. Many icons are, however many are not, as other Orthodox Christian cultures have their own traditional styles of art and many icons exist, painted in a Western style. Sacred images from other cultures that follow a consistently repeated pattern might also be called icons. Cycladic Bronze Age figurines, Ghanaian akuaba goddess carvings, Hopi katchina dolls, Tibetan thangkas are just some of the numerous traditional artistic expressions from around the world that are “icons” in this broader sense. It is not style that makes a painting an icon, it is subject, meaning and use. Most icons are two-dimensional; mosaics, paintings, tapestries, enamels, miniatures, however, many ancient icons are three-dimensional, as well. Orthodox Icons The icon lies at the heart of Orthodox Christian belief implying a cosmology that defines Christ as both human and divine. The very legitimacy of icons was passionately fought over, with icons for a period, being subject to iconoclastic destruction. At last, in 757AD, the Second Council of Nicaea finally decreed icons legitimate and that their veneration only means reverence for the personage represented not for the image itself. The doctrine said that once God had appeared on earth in human form (as Christ) the image and form itself could itself contain the divine. This applies to the subsequently developed icons of many saints, prophets and festivals of the year. Byzantine Icons hence developed and were held within this dogma. The forms, having been defined, became ever more rigidly proscribed. One would think, perhaps, that icons are therefore not capable of expression or variation. But if we examine the lineage we find that along the apparently unchanging iconography there were masters who were able to bring a highly individualized vision to the traditional image. Andrei Rublev and his master Theophanes the Greek in Russia, and Andreas Ritzos in 15th Century Crete are some of the great masters of the medium. Later icons of recent centuries tended to degenerate to mere dogma and slavish copying, losing their power. In all cases, from any culture, images that are revered become icons of the energy depicted. The repeated and recognized form takes on a sacred dimension as it offers a doorway into the transformed awareness embodied by the icon. The images are not worshipped as an external power, they become our associates in the purification and elevation of our spirit. Gods, goddesses, bodhisattvas, saints, angels and the orders of sacred beings are not merely represented but through their form, when activated by contemplation and intention, transmit their healing powers. Praying with an icon admits the person to the divine vision in a mystical and ecstatic communication. |